“All employees must be directly involved, learning about innovation. And they must have direct experience with it. New governance gets managers more involved in the decision making…. Only when innovators operate with the credibility of leaders will innovation become a productive part of the everyday business.” – Craig Wynett, a key driver of P&G's pre-eminence in innovation

Successful transformation on a large scale, in any organization, requires lots of behavioral change. In government agencies, the challenge is much tougher – because the need for change is seldom driven by the proverbial “bottom line” – though customer service expectations are as high as those measured in the private sector, particularly during recessionary periods when the demand for government services tends to rise. To sustain behavioral changes, the major focus of most big transformation endeavors, those who do the work must be engaged in redesigning the processes that will influence their future activities and outcomes. This is the critical, and often weakest, link between people and processes. If it is not clearly established, and maintained over time, organizational transformation will prove to be neither optimized nor sustainable.

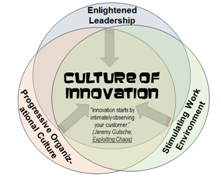

Before launching a complex transformational initiative in a government agency, a culture of innovation must be created and nurtured – similar to the way one should prepare the ground and soil for growing (and cultivating) a new garden (on a grand scale). A new approach to the work environment is needed, one in which everyone sees the need to improve his or her job, as part of an accepted “duty” to the greater good of the larger enterprise – where success is fed by the crucial synergies that should emerge from the critical intersection between enlightened leadership[1], a progressive organizational culture[2], and a stimulating work environment[3].

a) Enlightened leadership – This is manifested in different ways in different contexts, depending on readiness, factors that shape change, and leadership opportunities. However, the key characteristics of plurality, functionality, problem orientation, and change space creation are likely to be common to all successful, leadership-led change [initiatives][4].

b) Progressive organizational culture – “A culture is about everyone belonging to something they believe in… something of great and higher purpose. The fundamental motivation for people in a business is to do something important . . . that is of greater importance than themselves as individuals.[5]” Another key aspect of a progressive organizational culture is how the internal culture manifests itself externally, with respect to customers, business partners, and all other stakeholders in the enterprise.

c) Stimulating work environment – There are key elements that constitute a motivational workplace environment that are important to people regardless of generation, gender, or temperament.

These core elements, when in place, promote people to thrive and give their best. Intellectual stimulation means new, creative and innovative ways of doing the conventional. It is defined as the degree to which everyone encourages others to be creative in looking at old problems in new ways, while maintaining an environment that is highly tolerant. Often, intellectual stimulation also entails questioning old assumptions and the status quo[6].

Change management experts often emphasize the importance of establishing organizational readiness for change and recommend various strategies for achieving it. In my work with numerous government departments and agencies over the years, a clear emphasis on culture has been increasingly noted, actually peaking of late —for several (apparent) reasons:

There’s Seldom Much Doubt about the Meaning of Culture

Culture is a set of values, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors shared by a group of people. Organizational culture is a concept in the field of organizational development and management that describes the attitudes, experiences, beliefs and values of an organization. It has been defined as “the specific collection of values and norms that are shared by people and groups in an organization that control the way they interact with each other and with stakeholders outside the organization[7].” It’s the way individuals interact with others, the way they go about work and the practices of their environment. Cultures can range from being traditional and hierarchical to casual and collaborative. Building and sustaining a solid positive organizational culture is one way of showing that people are your most valuable asset.

Organizational culture directly influences the identity of the organization and the behavior of its employees because it is part of the informal rules that guide the behavior of its personnel and govern its operations within established limits. Most government leaders confirm that culture is all about values and distinctive behaviors that determine how activities are accomplished within their respective agencies (and, with their business partners). Many also acknowledge the importance of a high-performance culture to their organization’s chances of success. Yet, many are disappointed by the enormous gap they see between their current and desired cultures. Others are confused, especially newly appointed leaders, because they don’t know why their current culture is unsuited to today’s operational needs —or what steps they should take to get to a better place, where a high-performance culture wouldn’t seem like such an aspirational goal.

Many leaders, however, are uncertain about how to gauge the extent to which their organization is ready for change.

Organizational Readiness for Change

Organizational readiness for change[8] is a multi-level, multi-faceted concept. As an organization-level construct, readiness for change refers to stakeholders' shared resolve to implement change (change commitment) and shared belief in their collective capability to do so (change efficacy). Organizational readiness for change varies as a function of the extent to which stakeholders value the change and how confident they are that these key determinants of implementation success are both understood and can be satisfactorily addressed: clarity of mission demands, adequacy of resource availability, continuity of situational awareness, and the agility needed to appropriately make course corrections in the face of unanticipated circumstances (i.e., without abandoning the mission). When organizational readiness for change is high, affected stakeholders are more likely to commit to change, exert greater effort, exhibit greater determination, and display more collaborative behaviors. Transformation leaders need to see sufficient evidence that these stakeholder actions and attitudes have reached critical mass, or the tipping point in favor of mission success, before launching a major transformation initiative. Indeed, a failure to establish sufficient readiness for change accounts for half of all unsuccessful, large-scale organizational change efforts[9].

Drawing on Lewin’s three-stage model of change[10], change experts have offered various strategies to build readiness by 'unfreezing' pre-existing mindsets and creating stimulus for change. These strategies include highlighting the gaps between current and desired performance levels, generating discontent with the status quo, promulgating a compelling vision of a future operating paradigm, and building confidence in the achievability of the desired future state[11].

Changing the direction of any organization requires that it free itself from old methods, practices, and habits – cautiously and systematically. Starting that progression can be as simple as finding a way to enlist the support of selected, more progressive leaders within an agency, to identify main conflicts and other impediments to change. The agency’s core values must also be revalidated. Then, leaders can address problem areas head-on, by reinforcing an acceptable culture of change, and rewarding behaviors that advance and promote that model.

It must be also acknowledged that current organizational structures and available resources also shape readiness perceptions. In other words, organizational members take into account the organization's structural assets and deficits in formulating their change effectiveness judgments. Also, organizational readiness for change is situational; it is not a general state of affairs. Some organizational features do seem to provide a more receptive context for innovation and change[12]. However, receptive context does not translate directly into readiness. The content of change matters as much as the context of change[13].

A healthcare organization might, for example, exhibit a culture that values risk-taking and experimentation within a positive working environment (e.g., good management-clinical relationships), and a history of successful change implementation. Yet, despite this apparent receptiveness to overall change, this organization could still demonstrate a high readiness to implement electronic medical records, but a lower readiness to implement an open-access scheduling system[14]. Commitment is, in part, change specific; so too are effectiveness judgments. It is possible that an apparent receptivity to change is a necessary but insufficient condition for readiness. For example, good managerial-clinical relationships might be necessary for promoting any change even if it does not assure the commitment of clinicians to implementing a specific change. Also, the two most basic indicators of organizational readiness for change – i.e., change commitment and change utility – are conceptually interrelated, and perhaps empirically correlated. Low levels of confidence in one's capabilities to execute a course of action can impair one's motivation to engage in that course of action[15]. Likewise, fear and other negative motivational states can lead one to underestimate or downplay one's own judgment of capability[16]. These cognitive and motivational aspects of change readiness can be expected to vary congruently, but not perfectly.

At one extreme, organizational members could be very confident that they could implement an organizational change successfully, yet show little motivation to do so. The opposite extreme is also possible. Organizational readiness is likely to be highest when organizational members not only want to implement an organizational change, but also feel confident that they can do so.

What situations are likely to produce a shared sense of readiness? Consistent leadership messages and actions, information sharing through social interaction, and shared experience--including experience with past change efforts – can promote commonality in organizational members' readiness perceptions[17]. Conversely, organizational members are unlikely to hold common views of readiness when: a) leaders communicate inconsistent messages or act in unpredictable ways, b) intra-organizational groups or units have limited opportunity to interact and share information, or c) organizational members do not have a common basis of experience[18]. Intra-organizational variability in readiness perceptions suggests lower organizational readiness for change and may indicate problems in implementation efforts that demand coordinated action among interdependent stakeholders.

Countering resistance to organizational change requires strong leadership, effective communications and strategic (rather than reactionary) approaches, but it can be done. With careful identification of the current culture and a strong idea of where you want to go, you can engineer the culture of your organization.

The state of organizational readiness will be achieved when organizational members are committed to implementing change, and demonstrating confidence in their collective abilities successfully achieve the agreed set of desired outcomes. A recognition that collective behavior changes are necessary in order to effectively implement the needed change, is perhaps the best indicator that the anticipated benefits of the transformation initiative are likely to be realized.

"The future is already here -- it's just not evenly distributed"

This observation by the novelist William Gibson[19] is applicable, in my view, to nearly every transformation initiative in virtually any government organization. Indeed, there is often more variation among workgroups within a single department or government agency than one would find across multiple agencies. A given organization reviewing its customer engagement success is likely to find that teams in some locations provide outstanding service and satisfy most of their customers, while others alienate nearly every customer they encounter.

Looking within the organization for pockets of distinction, those places where excellence thrives, can also be a good way to improve customer service, rather than looking outside the department of agency for innovative solutions. Teams that are already embracing change can provide best practice examples to other parts of the enterprise. Also, key stakeholders who already acknowledge the need for change are more likely to support changes as they are implemented.

Processes, the intermediate steps by which organizational goals are achieved, often determine whether those goals are achieved efficiently, or at all. To be successful in improving the many complex and interrelated processes that influence the delivery of government services to those that need (or are entitled to) them, sound systematic approaches must be applied to the implementation of large changes. An integral dimension of success will be the full engagement of all stakeholders in process redesign. Even when conducted in a rigorous fashion, process redesign is not always successful. As has been demonstrated many times before in government entities, the most common sources of failure are related to poor staff acceptance, failure to actually change behaviors, and inadequate leadership. Many federal agencies face extraordinary challenges in scaling change across their organizations because of their great size and extensive geographical coverage. A key element of success, given the scope and complexity of the transformations undertaken in such circumstances, is the active engagement of frontline staff – on all fronts –, who must be involved in the design and implementation of the needed changes. This will increase the probability that processes, procedures, and business logic will be properly redesigned and that all employees will wind up modifying their behaviors.

The Bottom Line

Successful leaders constantly face resistance to change as they facilitate movement from a culture of opposition to one that fosters innovative ways of thinking. However, forward-thinking organizations around the world have embraced organizational change management to break through those outmoded perspectives. A significant component of this process requires culture “re-engineering,” a wholesale evaluation of your agency’s culture-derived behaviors. A new culture of innovation must be established, prior to the launching of a major transformation, especially in a government organization, to allow all affected stakeholders a bit of time, and space, to come to terms with the new reality being promulgated by bold, energetic, and empowered leaders. Changing the direction of any organization requires that it unfreeze itself from old ways of doing business, carefully and methodically. For organizational readiness, the key question is: regardless of their individual reasons, do organizational members collectively value the proposed changes enough to commit to their implementation? Until that question is answered in the affirmative, your organization is not ready for change – which means that the leaders of your agency must pay additional attention to building a sustainable culture of innovation.

[1] The key to enlightened leadership lies in showing those who would be change agents how to capitalize on their organization's greatest asset: the under-utilized talent, expertise, and energy of its existing staff. Enlightened leaders aim to maximize the contributions of all employees -- by sharing information, decision-making, and planning with them -- creating a shared culture of organizational goals, strategies, and methods. This involves planning, communication, and motivational tools, to support employees in effecting the positive changes that will make the difference in achieving their organizations' bottom-line goals. (Oakley and Krug, Enlightened Leadership: Getting to the Heart of Change)

[2] Without a solid, symbiotic relationship between leaders and managers, a business cannot maintain a healthy organizational culture. (Jason Gillikin, “Management Vs. Leadership in a Healthy Organizational Culture”)

[3] Today, an organization’s success depends on the collective wisdom of all its employees. Leaders play an important role in guiding workers to use their collective power effectively and in developing an environment that fosters trust and respect. (Eunice Parisi-Carew & Lily Guthrie, “Creating a Motivating Work Environment”)

[4] From “Global Leadership Initiative Research Study,” which examines leadership in the change processes of fourteen capacity development interventions in eight developing countries. The paper explores what it takes to make change happen in the context of development, and in particular, the role leadership plays in bringing about change. (Andrews, McConnell and Wescott, Development as Leadership-led Change: A Report for the Global Leadership Initiative)

[5] Mark Templeton (Citrix CEO)

[6] Hetland and Sandal, Transformational Leadership in Norway

[7] Social/Human Dimensions of Web Services: Communication Errors and Cultural Aspects (Charles & Gareth.

[8] See, for example, “Tips and Suggestions for Enhancing Organizational Readiness,” promulgated by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

[9] Leading Change, J.P. Kotter

[10] Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers, Kurt Lewin.

[11] Readiness, action, and resolve for change: do health care leaders have what it takes?, C. Hardison

[12] No Magic Targets! Changing Clinical Practice to Become More Evidence Based (S. Dopson, L. FitzGerald, E. Ferlie, J. Gabbay, and L. Locock)

[13] Receptivity to Change in a General Medical Practice, British Journal of Medicine (J. Newton, J. Graham, K. McLoughlin, and A. Moore)

[14] Shaping Strategic Change: Making Change in Large Organizations: the Case of the National Health Service (A,M, Pettigrew, E. Ferlie, and L. McKee)

[15] Self-efficacy: the Exercise of Control (A. Bandura)

[16] Self-efficacy Theory: An introduction (Edited by J. E. Maddux

[17] From Micro to Meso: Critical Steps in Conceptualizing and Conducting Multilevel Research (K.J. Klein and S.W.J. Kozlowski)

[18] Indicators of Organizational Readiness for Clinical information Systems Innovation (R. Snyder-Halpern)

[19] Gibson is reported to have first said this in an interview on Fresh Air, NPR (31 August 1993)

There are no products in your shopping cart.

| 0 Items |

|

|

Important points have been